In the beginning there were three record labels putting out music from America’s burgeoning punk scenes. There was Bomp! In Los Angeles, Titan in the midwest, and, in New York City, Ork records.

Ork was founded by Terry Ork (born William Terry Collins) in 1975. Described by Patti Smith Band member Lenny Kaye as a “cherubic individual”, Ork had moved from California to New York as part of Andy Warhol’s entourage at the Factory, helping out on Warhol’s films, and working at the original iteration of Interview magazine. He hung around the Factory until he was escorted out of the building under a cloud of suspicion of selling black market copies of Warhol’s screenprints.

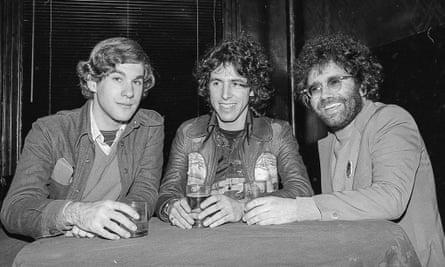

In need of a job, Ork went to work at the Cinemabilia bookstore, where he met punk pioneer Richard Hell. Despite having no experience, soon afterwards Ork started managing Hell’s band, Television. “He didn’t come from the rock’n’roll world, but he was definitely enjoying his entrance into it,” says Kaye.

“Terry definitely had a tremendous amount of charisma,” says Jane Fire, whose band the Erasers is featured on a recently-released Ork records retrospective box set. “He had kind of a worldliness about him. He just was cultured. I mean, he could talk to you about Jean Genet and the Ramones. He was just as versed in both things.”

Before launching his record label, Ork was already a regular at CBGBs, well known on the scene – enough to feature in the 2013 film CBGB, where he was played by The Big Bang Theory’s Johnny Galecki.

“I began hanging out at CBGBs with Patti Smith on Easter of 1974,” says Kaye. “That was the first time that we saw Televsion. I met their manager Terry Ork.”

Kaye noticed that Ork wasn’t a stereotypical band manager, but was more interested in helping the band achieve their purpose more than profits. It’s an ideology he carried over into his record label, Ork records, which was eventually buttressed by his partner, Charles Ball, and two Hasidic men known as “the Hats” who helped finance the record label by, it was rumoured, dealing drugs.

“Ork records began as a way to present some of the local bands that CBGBs featured,” said Kaye. “Looking at the box set, it surprises me how deep their musical sensibilities went.” CBGBs was the crucible for a lot of mould-breaking bands – the Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads – but while Ork released tracks by more well-known acts like Television, Richard Hell, the Feelies and Big Star frontman Alex Chilton, the bulk of their catalogue was made up of scratchy, trebly, energy-infused bands that never quite made it to that level of fame.

The likes of Cheetah Chrome, the Erasers, Marbles, Idols and Chris Stamey and the dBs were the more obscure bands of an already underground scene. “The scene was so much bigger than Blondie and Television and the Ramones,” says Fire. “A lot of these bands, I mean, I guess we fit in that category too, were so important to the scene, but never got their due. If Terry hadn’t been around, they may have been forgotten.”

The Numero Group, known for re-releasing back catalogues and out of print albums, stumbled on the story of Ork records when one of the owners, Rob Sevier, bought a few of the 45s released on the label and decided to collect the lot. His partner Ken Shipley soon caught the fever, too, and they decided to assemble Ork’s first full retrospective. Some of the songs hadn’t even been released, thanks to Ork’s flakiness about paying the studio bills. “This was like the first punk label in the world,” said Shipley. “Their sole mission was to document an emerging scene.”

And what a scene it was. “I don’t think we ever realized how amazing it was,” says Fire. “We had this loft and there were always these big parties where Allen Ginsberg and Iggy Pop would come by and Johnny Rotten would stay at our house. But you don’t really realize what you’re in when you’re in the middle of it.”

Ork records sputtered to a halt in 1980, Ork fleeing to Europe and then Los Angeles. He spent time in prison for fraud, adopted a new pseudonym and edited a film magazine, finally dying of colon cancer in 2004. The Numero Group leapt at the chance to allow his label to reclaim its place in history. However, as excited as they were to unleash Ork’s musical vision on the world (again), Shipley and Sevier had their work cut out.

“Terry Ork is dead, and he didn’t marry, he didn’t have any children, how are we going to do this?” said Shipley. “There’s no paperwork here, there’s no contracts. This isn’t what they did.” Without any other option, Numero set out to contact every artist who had released music on Ork to find out what it would take to re-release the songs.

“We felt like Richard Hell, Television and the Feelies were going to be the biggest stumbling blocks, and it was a good thing that we approached them first because the Feelies took the longest to coming around,” said Shipley. Hell told them he would participate, but only if they got every other act on board. ”We kind of gambled, and said OK, we have to get everybody,” said Shipley. “And if we have to get everybody, let’s get everybody. We started finding people who were just tertiarily involved with the scene.”

Because of the type of reissues that they do, Numero Group is used to doing a fair amount of detective work. “We use the same computer systems that they use to find deadbeat dads and credit card debtors,” says Shipley.

They hit the motherlode when they got in touch with the owners of an Ithaca, New York, record store called Angry Mom Records. “He had bought the contents of a storage space that belonged to Terry Ork’s partner Charles Ball, and in there came lots of records, but more importantly, all the paper,” said Shipley.

As the project’s scope became apparent, the partners threw themselves into it, sometimes at a risk to their own business relationship. “We fought about the sequence. We fought about the art, we fought about everything. Just because when you really love something, you want it to be perfect,” said Shipley.

It took Shipley a year to write the book that accompanies the box set. “It’s 190 pages, and it’s close to 70,000 words,” he says. The book and the musical retrospective offer a portrait of a man, Ork, while shining a new light on New York’s punk scene. “The story has never been told,” said Shipley. “All these people are only getting older, some of them are dead. If you don’t tell it right now, there’s never going to be an opportunity to tell it.

“It’s not about the Ramones and it’s not about Blondie and it’s not about Talking Heads. They already have their own legacy sealed up,” said Shipley. “This is like there’s this world that existed after dark and, it was gone like that [snaps]. And the story that’s inside of them – this is the account. It will be here forever. We set it down.”

“I really believe that they helped document a very important scene and made it real,” said Kaye.

CBGBs may be a clothing store now; the Bowery has some of the most expensive real estate in Manhattan; and the Ramones may be on T-shirts sold at Urban Outfitters, but thanks to Numero, Ork records won’t be forgotten, which is good news for those who knew and loved Terry Ork. “He deserves that,” said Fire. “At least that.”

- Ork Records is out now on Numero Group.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion