“DA Pennebaker is the grandaddy of the documentary – he didn’t buy his camera, he built it,” explains Joseph Baldassare, curator of a new exhibition about Pennebaker’s film Don’t Look Back. It famously chronicled Bob Dylan’s pivotal 1965 tour of England and his transformation from a polite leading light of the marginal folk scene into an incendiary figure in the cultural mainstream.

“Very few people change the way of the world,” says Baldassare. “To me there is before Elvis and after Elvis, before Cassius Clay and after Muhammad Ali, and before Bob Dylan and after Bob Dylan. In Don’t Look Back we have the rare vantage point of seeing that moment just before.”

Shot handheld on black-and-white 16mm film, Don’t Look Back invented the “rockumentary”. Its fly-on-the-wall style flew in the face of contemporary cinematic convention, and its reputation and influence has steadily grown since its release in 1967. In 2014, the British Film Institute’s authoritative poll of movie industry experts ranked Don’t Look Back as one of the 10 best documentaries of all time.

Since the mid-1950s Pennebaker had been a pioneer of the observational “direct cinema” style, and had even helped develop the small synchronised sound and vision system which enabled it. While making films for Life magazine, he was looking for a more personal project when he met Bob Dylan in a bar in Greenwich Village. “He [Dylan] said: I have an idea for a film where I write out all the words to this song on pieces of paper, and I’ll just throw them down as I read them,” Pennebaker recalls. “I said: that’s a fantastic idea.” This eventually became the famous Subterranean Homesick Blues “video” (actually the opening sequence in Don’t Look Back).

Pennebaker was not attracted to Dylan because he was a celebrity – in fact, quite the opposite. “I was interested in real people and why they did things, or how they did things. And the only way to find that out was to follow them,” he says. “I didn’t know him [Dylan] that well, I didn’t know who he was really. But the idea of going with a musician on a tour and being able to photograph him – both when he performed and when he didn’t perform – that seemed to me an interesting idea.”

So did this idea turn out? “Dylan is an interesting person to watch because he is constantly creating himself, and then standing back and trying to witness it,” says Pennebaker with typical understatement. The movie is mesmeric: while it features spellbinding snatches of a musician performing at the height of his powers, the off-stage drama is just as enthralling. Arriving in England, Dylan is all politeness and charm in the face of a media circus intent on turning him into an easy-to-understand cardboard cutout. But as the chaotic tour wears on, he becomes increasingly abrasive and angry, mercilessly mocking a backstage interloper and demeaning a reporter from Time magazine.

“Some people thought he looked like a total shit, you know. I mean, people make up their own mind about what he is like from watching the film and that’s OK. I can’t change that,” says Pennebaker, who didn’t find Dylan at all difficult to work with. “He was very easy, we got along fine. I mean, we’re still partners.”

Despite being shot in black and white over half a century ago, Don’t Look Back still looks contemporary. It was certainly way ahead of its time in the 1960s. “The people who distributed films didn’t even want to look at it,” says Pennebaker. “For them, films were made with people who were very well known, celebrities … The way they were filmed was always in perfect clothes, perfect surroundings, and whenever they spoke the voices were perfectly heard. It was hard. We distributed it ourselves, we couldn’t get a distributor.”

Having left the corporate structure of Life magazine, Pennebaker had no production funding for Don’t Look Back. “If you’re only one person and you’re shooting with a camera that you built yourself, it’s not so expensive,” he explains. “You didn’t need a crew. You didn’t need lights because the film was pretty fast. You didn’t need any extra things. You didn’t have to have big studios and expensive makeup and all the things that Hollywood had put on to the films, because they weren’t necessary. And that’s what I did, and that’s what we still do.”

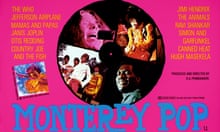

Pennebaker is still making films in his signature style with his directing partner Chris Hegedus, and the influence of his earlier work is still being felt across the spectrum of moving image. With Monterey Pop, Pennebaker practically invented the concert film at a 1967 festival featuring Janis Joplin, The Who and a guitar-burning Jimi Hendrix. 1993’s The War Room, which followed Bill Clinton’s election campaign, became a blueprint not only for subsequent documentaries but also for dramas (such as The Thick of It and Veep). In 2012, an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement was awarded “to DA Pennebaker, who redefined the language of film and taught a generation of film makers to look to reality for inspiration”.

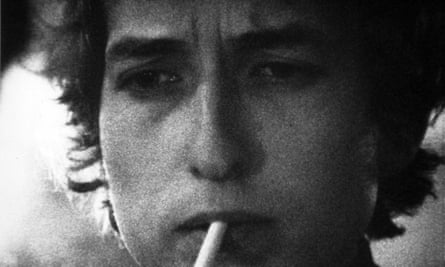

The Don’t Look Back exhibition at New York’s Morrison Hotel Gallery breaks yet more new ground for Pennebaker, as it includes new photographs made from stills from the film. “The moments before a performer takes the stage, they navigate a wave of reflection, preparing for what is about to take place,” explains curator Baldassare, who selected the stills for the photographs. “In creating this exhibit, I looked for those moments.”

Pennebaker never had any intention of following in the footsteps of his father, who was a photographer. But at the age of 90 he seems happy to have done so. “I never thought of myself as a photographer,” he says, “but when I see these pictures I’m quite impressed with how some of them have turned out.”

Don’t Look Back exhibition is at the Morrison Hotel Gallery, 116 Prince Street, New York, 20 May to 14 June.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion