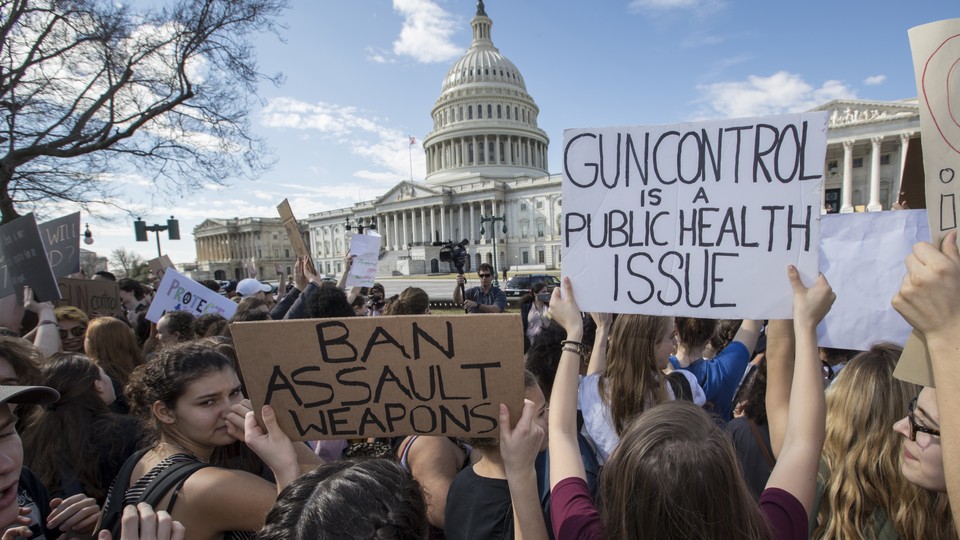

Where Gun-Control Advocates Could Win in 2018

There’s a clear path to rebuilding a House majority that supports restrictive measures. It runs through America’s suburbs.

The shifting geography of the electoral battlefield is providing gun-control advocates their best opportunity in years to tilt the balance on the issue in Congress.

Since the early 1990s, the National Rifle Association has sustained an impregnable congressional blockade against new gun-control measures. But the weakest link in that chain has always been the Republican-held suburban seats in the House of Representatives, where many voters support reasonable limits on gun access.

Even before the mass shooting at a Parkland, Florida, high school last week, Donald Trump’s unpopularity with college-educated voters was pushing those seats to the center of the midterm battle for control of the House. Now, the increased attention to gun issues could widen the wedge between suburban Republicans and the white-collar voters already recoiling from Trump’s tempestuous presidency.

“Where it coincides with the political realignment that’s occurring under Trump, the gun issue puts at risk a lot of these Republicans who have represented … suburban districts,” said Peter Ambler, the executive director of Giffords, the gun-control advocacy group founded by former Representative Gabrielle Giffords.

During his first term, then-President Bill Clinton overcame the NRA’s resistance to pass the 1993 Brady bill mandating background checks for most gun sales and the 1994 ban on assault weapons. Since then, two major dynamics have tilted the balance in the House toward the NRA and its allies.

The most visible change has been the GOP’s success at ousting Democrats in dozens of rural and small-town districts and replacing them with pro-gun-rights Republicans. But “visible” doesn’t necessarily mean “dispositive”: The Democrats’ rural losses didn’t change the legislative balance as much as commonly assumed, because most of the Democrats who formerly held those seats also voted against gun control. In 1993, 69 House Democrats opposed the Brady bill; in 1994, 77 opposed the assault-weapons ban. The rural realignment largely replaced Democrats opposed to gun control with Republicans even more ardently opposed.

The more consequential change has come in suburban areas. Despite the widespread Democratic defection from outside the major urban centers, the Brady and assault-ban bills passed because Clinton drew support from dozens of suburban Republicans inside those metropolitan areas. Fifty-four House Republicans backed the Brady bill in 1993, and 38 supported the assault ban the next year; the latter number grew to 46 when the ban was included in the final version of Clinton’s crime bill. Of those 46 Republicans backing the overall bill, most were from heavily suburban, Democratic-leaning states, including eight from New York; five from New Jersey; and three each from California, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania.

In the years since, the GOP’s geographic base has shifted away from major metropolitan areas and its demographic base has tilted further toward older, blue-collar, evangelical, and rural voters. Reflecting those changes, GOP congressional leaders have tightened their alliance with the NRA and hardened their opposition to gun control. The remaining Republicans from suburban districts, even in the bluest states, have bent compliantly to that current. Compared with their counterparts in the 1990s, suburban House Republicans now vote much more in lockstep with the NRA.

In December, all but 10 suburban House Republicans voted for legislation to override individual state gun laws and require every state to honor a concealed-carry handgun permit issued in any state. In February 2017, all but two House Republicans (New York’s Peter King and Dan Donovan) voted to overturn a regulation from former President Barack Obama that required the Social Security Administration to share information with the national background-check system about anyone deemed incapable of managing their benefits because of mental illness.

Many of the Republicans who voted with the NRA on both measures represent white-collar suburban seats atop the Democrats’ 2018 target list. That includes GOP legislators near Denver (Mike Coffman); Los Angeles (Dana Rohrabacher, Mimi Walters, and Steve Knight); Minneapolis (Erik Paulsen and Jason Lewis); New York (Lee Zeldin); Northern Virginia (Barbara Comstock); Omaha (Don Bacon); Des Moines (David Young); Houston (John Culberson); and Dallas (Pete Sessions). Except for King and Donovan, every other top-target metro Republican—from Carlos Curbelo in Miami to Leonard Lance in New Jersey—who voted against the concealed-carry reciprocity bill voted for the repeal of Obama’s Social Security regulation.

Since Obama’s election in 2008, Americans have divided almost evenly in Pew Research Center polls on the core question of whether it’s more important “to protect the right of Americans to own guns or to control gun ownership.” But while whites without a college degree prioritize gun rights, about two-thirds of non-whites and three-fifths of college-educated white women put more emphasis on controlling guns. College-educated white men split about evenly.

That combination of attitudes makes gun control still a tough sell in most rural and blue-collar seats. But it means there’s a majority of voters for gun control in many of the suburban districts where Trump’s white-collar woes are already threatening Republicans. ABC/Washington Post and Quinnipiac University national polls released Tuesday found that about three-fifths of college-educated white men and two-thirds (or more) of college-educated white women support a ban on assault weapons—the Parkland student movement’s principal policy demand after the shooting.

That movement, now building toward a March 24 march on Washington, appears poised to provide what “the gun-control movement needs most: passionate people who want to get active,” noted University of California, Los Angeles, law professor Adam Winkler, who’s written extensively on gun issues. The small steps to restrict gun access Trump has floated in recent days are unlikely to pacify them.

Gun control still closely divides the country, and the Senate’s small-state bias means any measure controlling access to firearms faces a tight squeeze there. But there’s a clear path to rebuilding a House majority for gun control—and it runs directly through the white-collar suburban seats that already look like ground zero for 2018.