The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics will release February employment data this Friday, following a minor uptick in the unemployment rate during January. In his State of the Union address, President Donald Trump brushed aside that slight trend reversal, along with the partial shutdown’s contribution to it. He further claimed responsibility for historically low unemployment rates for black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans, though these groups have also experienced upticks from their recent lows. Regardless, such longer-term trends precede this administration and have only slowly eroded long-standing—and still glaringly present—disparities.

The claim that immediately followed was also patently misleading: “[U]nemployment for Americans with disabilities … has reached an all-time low.” While the president’s statement is technically true, it nonetheless obscures the considerable barriers to economic security for disabled Americans, which have led to yawning gaps between disabled and nondisabled workers in terms of rates of unemployment, labor force participation, income, poverty, and full-time work.

In keeping with a previous analysis, this column uses data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey and borrows the survey’s definition of disability: whether an individual identifies having “physical, mental, or emotional conditions that cause serious difficulty with their daily activities.” The column focuses predominantly on prime-age workers, those ages 25 to 54, thus controlling for the increasing likelihood of disability with age. However, it is important to note that a broader challenge of defining disability underlies discrepancies in pertinent data collection, as the definition of the term varies depending on what legislative lens is being used; it can take on different meanings according to the context.

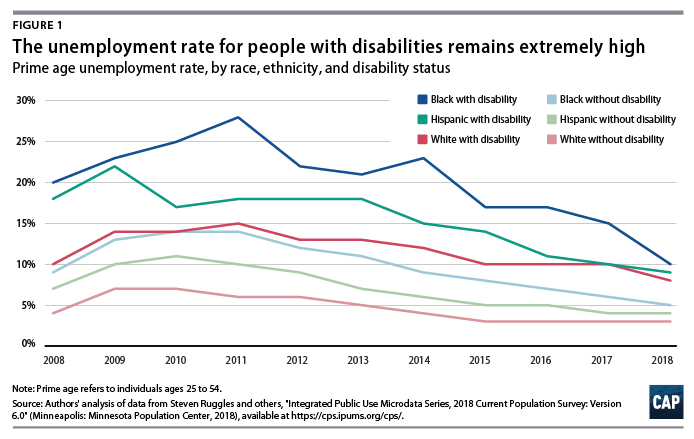

Unemployment rate, by disability status and race and ethnicity

Following the onset of the Great Recession, the gap between unemployment rates of disabled and nondisabled workers peaked at more than 9 percentage points—16.9 percent and 7.8 percent, respectively. That gap has just slightly narrowed over the past decade; however, unemployment has consistently remained around 8 percentage points higher for workers with a disability since 2008. This disparity is even more pronounced when disaggregating by race and ethnicity. Hispanic and black workers with disabilities experience staggering levels of unemployment, with the latter group experiencing unemployment as high as 27.6 percent in 2011. (see Figure 1) This underscores the devastating effects of the recession on black and Hispanic individuals, people with disabilities, and, especially, those at the intersection of these groups.

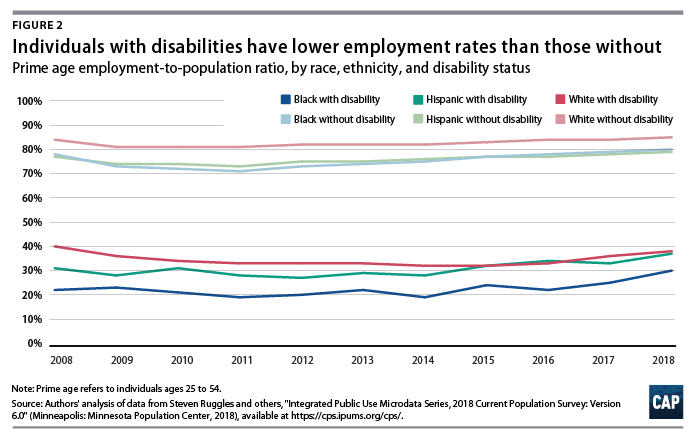

Employment-to-population ratio, by disability status and race and ethnicity

The employment-to-population ratio for workers without a disability is more than double that of disabled workers. This highlights the barriers that disabled individuals encounter when attempting to enter the labor force, such as lack of transportation; lack of legally required, reasonable accommodations on the job; and lack of training for both the employer and the employee. Once again, these barriers disproportionately affect disabled black and Hispanic individuals with disabilities. For the past decade, the employment-to-population ratio for white individuals with a disability has hovered between 33 percent and 40 percent; in contrast, the ratio for black disabled individuals has remained close to 20 percent—only recently approaching 30 percent. Disabled Native Americans share a similarly low rate, and, in general, these two groups—black and Native American individuals—experience the highest rates of disability.

Educational and geographical factors are other important determinants to employment. Disabled adults with a college degree have an employment rate that is 10 percentage points lower, at 59 percent, than that of all nondisabled adults with a high school diploma or less—69 percent. Furthermore, disabled Americans are half as likely to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher. Variations in employment rates by metropolitan area are almost certainly a reflection of municipal provision of accessible transportation and housing. A lack of accessible housing is closely associated with homelessness, as 40 percent of homeless people report having a disability. Employer discrimination can also partly explain the low participation rates among people with disabilities—especially when it works in tandem with racial or gender discrimination.

Access to health care is one of the biggest impediments to employment for disabled people, as health insurance is critical for individuals with disabilities. But prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), often the only way for many to gain affordable access to health care was to turn to programs such as Supplemental Security Income and Social Security Disability Insurance—and these programs limit participants’ ability to earn income. The ACA freed up many disabled workers to join the workforce, but lack of access to affordable health care continues to present a barrier to work, particularly in states that have refused to expand Medicaid.

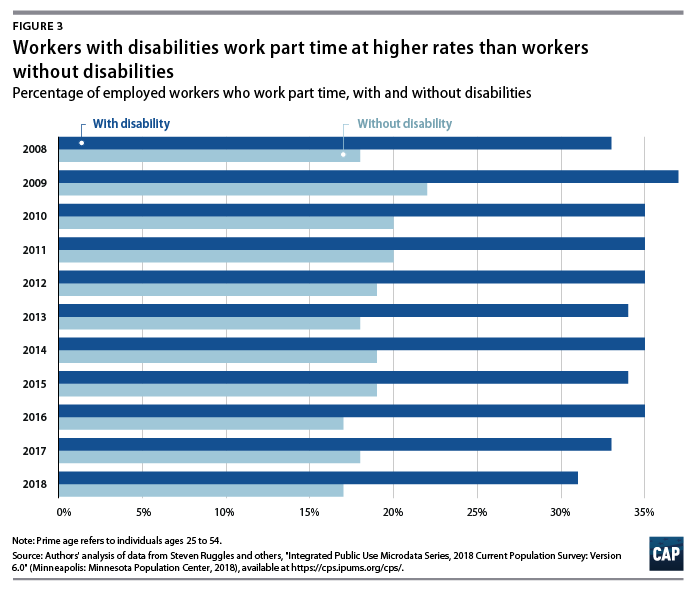

Workplace accommodations and part-time work

Lack of access to and employer knowledge about reasonable accommodations also creates unique constraints for disabled workers. Unfortunately, time and again, businesses have refused to comply with Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements for “reasonable accommodations,” which the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission defines as “any change in the workplace or in the way things are customarily done that provides an equal employment opportunity to an individual with a disability.” But even though providing accommodations for folks with disabilities is often simple and inexpensive, employers frequently far overestimate or overstate the cost.

Because of the challenge they face gaining appropriate access to transportation, an accessible work environment, and other reasonable accommodations, disabled workers often are more likely than nondisabled workers to be self-employed. Similarly, they are roughly twice as likely as nondisabled workers to work only part time. Not only do part-time and some types of self-employed work provide significantly less earning potential than full-time employment, but they also often lack benefits such as health insurance, paid family leave, and medical leave.

The low employment rates and high levels of part-time work for individuals with disabilities are also driven in part by the daily costs required for them to lead a secure life, as it is often both challenging and costly to find accessible transportation, housing, and work environments. People with disabilities may need various services and supports, such as personal attendant care, in order to work. As is required by Title I of the ADA, if someone needs an accommodation on the job site, an employer has to provide it. Yet, for time outside of the workplace, these supports are not covered through most health insurance plans and are therefore out of reach for the many who cannot afford them. This is especially onerous for those whose incomes and assets put them just beyond eligibility for Medicaid or Supplemental Security Income, leaving them in a perpetual struggle for upward mobility.

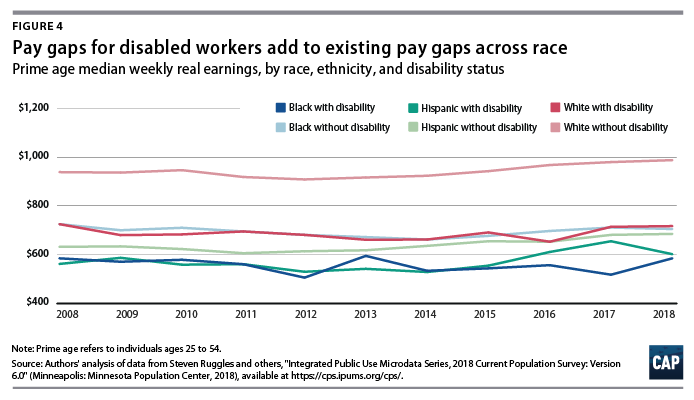

Income and poverty, by disability status and race and ethnicity

Those who do overcome these barriers to employment still face lower wages and higher poverty rates on average. Disabled workers experience nearly double the poverty rate of nondisabled workers and are much more likely to live at or near the poverty threshold. Given these realities, top-line unemployment figures alone are misleading indicators of economic security. Considering the prevalence of disability, this is critical cause for concern. One in 4, or 46.2 million, Americans ages 18 to 64 had a disability in 2014, while 1 in 7, or 29.1 million, had a severe disability. Moreover, only one-third of those with a severe disability in 2014 were employed, and these individuals made only $23,523 in median annual earnings—compared with $27,080 for all disabled workers in this age group.

While an outdated minimum wage already makes it increasingly difficult to keep up, the confluence of inaccessibility, discrimination, and lack of adequate health and social insurance significantly erodes the earning potential for those with disabilities. That difficulty is even more pronounced for the roughly 420,000 disabled people working under a program that allows a subminimum wage, commonly called Section 14(c) employment under the Fair Labor Standards Act. The last time this program was analyzed nearly two decades ago, the then-General Accounting Office found that more than half of such workers made less than $2.50 an hour. Furthermore, less than 5 percent actually transitioned into the formal workforce, counter to the program’s original intention following its creation in the 1930s.

Once again, at the intersection of disability and race and ethnicity, wage data yield startling observations. For black and Hispanic individuals with disabilities, already low pay is compounded by the reality of discrimination. In 2018, disabled workers as a whole made approximately $200 less per week than nondisabled workers. Yet black and Hispanic disabled workers earned roughly $400 less per week than their white nondisabled counterparts, representing the magnitude of this combined disadvantage.

Conclusion

Regardless of whether Friday’s report imparts an optimistic picture of the economy, a closer look at the economic reality for those who face systematic disadvantages in the labor market serves as a reminder of the critical need for investments in programs that provide basic living standards nearly three decades after the passage of the ADA. And though robust overall growth should be hoped for, policymakers should bear in mind which workers are still being disproportionately left behind in today’s labor market.

Nathan Smith is an intern for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. Galen Hendricks is a special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center. Daniella Zessoules is a special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center. Olugbenga Ajilore is a senior economist at the Center. Michael Madowitz is an economist at the Center.