Too Far Too Often

Energy Transfer Partners’ Corporate Behavior On Human Rights, Free Speech, and the Environment

Published: 06-18-2018

Download: PDF

UPDATE OCTOBER 2018 – Still Too Far: Energy Transfer Continues to Display Concerning Corporate Behavior.

Executive Summary

“The world is watching what is happening in North Dakota.”

—Mr. Alvaro Pop Ac, Chair of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, August 31, 2016 [1]

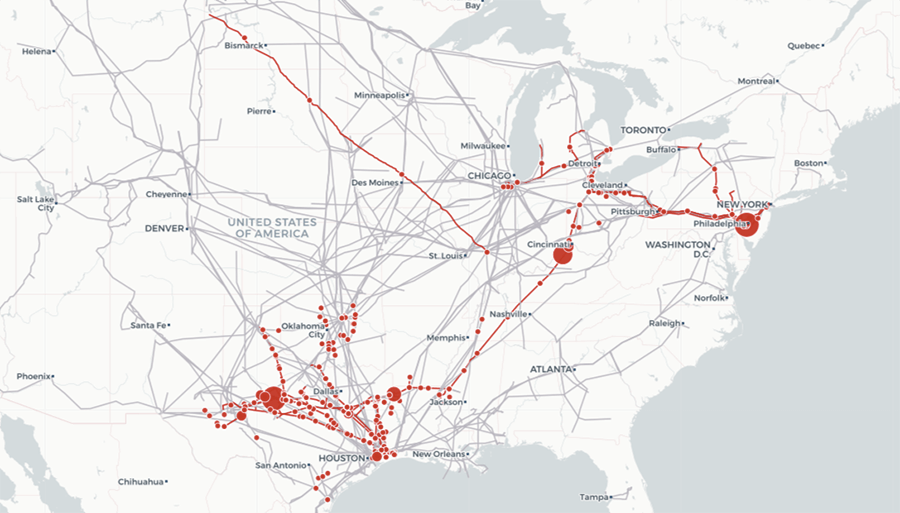

In December 2014, the Dallas, Texas-based company Energy Transfer Partners, L.P. (ETP) applied for permitting to build the $3.78 billion Dakota Access pipeline (DAPL). The pipeline was to carry crude oil from the Bakken shale oil field in northwest North Dakota, through North and South Dakota and Iowa, to an oil storage and transport facility in Illinois. By the fall of 2016, the controversial project had gained international attention and notoriety.

“Too Far Too Often” details the unethical and inappropriate tactics employed by ETP and related companies against opponents of DAPL, and highlights how, in spite of increased global scrutiny and intense criticism of ETP’s tactics at Standing Rock to intimidate and quash opposition, ETP continues to apply many of the same tactics and to display the kind of corporate behaviour that directly contributed to the controversy. ETP’s repeated use of these intimidation tactics means that the company and its financial backers risk facing similar controversies in other current and future projects.

Additional information and detail can be found in the relevant sections of the full report.

Violating Indigenous Sovereignty and Rights

- DAPL was approved without meeting international standards of free, prior, and informed consent of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.[2] For additional context see the section called “Tactic 1:Violating Indigenous Sovereignty and Rights” in the report.

- The company ignored calls for a voluntary halt in construction by the U.S. Departments of Justice, the U.S. Department of Interior, and the Army as controversy and questions around appropriate levels of assessment and due diligence arose in early fall 2016.[3]

- Dakota Access bulldozed an area of the pipeline corridor filled with Tribal sacred sites and burials. Documented in a UN report, a Sioux elder and cultural leader reported damage to at least 380 cultural and sacred sites along the pipeline route.[4]

Use of Intimidation and Threats to Free Speech

- Water Protectors and individuals opposing DAPL faced excessive force,[5] arbitrary arrests,[6] and lawsuits. For additional information about the use of force and intimidation, see sections called “Tactic 2: Silencing Free Speech with Intimidation” and “Tactic 4: Enabling Violence Against Communities” in the full report.

Intimidation Through Litigation Against Pipeline Opponents

- ETP and its related companies use SLAPP suits to attempt to silence and intimidate opposition. This included suing the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman and Tribal Councilman and several others “seeking restraining orders and unspecified monetary damages.”[7]

- After construction of DAPL was complete, in fall 2017, ETP filed a $900 million SLAPP suit against Greenpeace entities, Banktrack, and the movement, EarthFirst!, accusing the organizations of inciting and directing acts of “eco-terrorism.”[8]

- Arbitrary arrests and anti-free-speech lawsuits have become more commonplace across the sector in efforts to shut down pipeline opposition. However, ETP’s extreme use of litigation, including the use of RICO claims and high damages, could set a dangerous new precedent and have a chilling effect on the ability of individuals, communities, and organizations to vocalize and demonstrate opposition to future projects. See the section called “Tactic 2: Silencing Free Speech with Intimidation” for additional information.

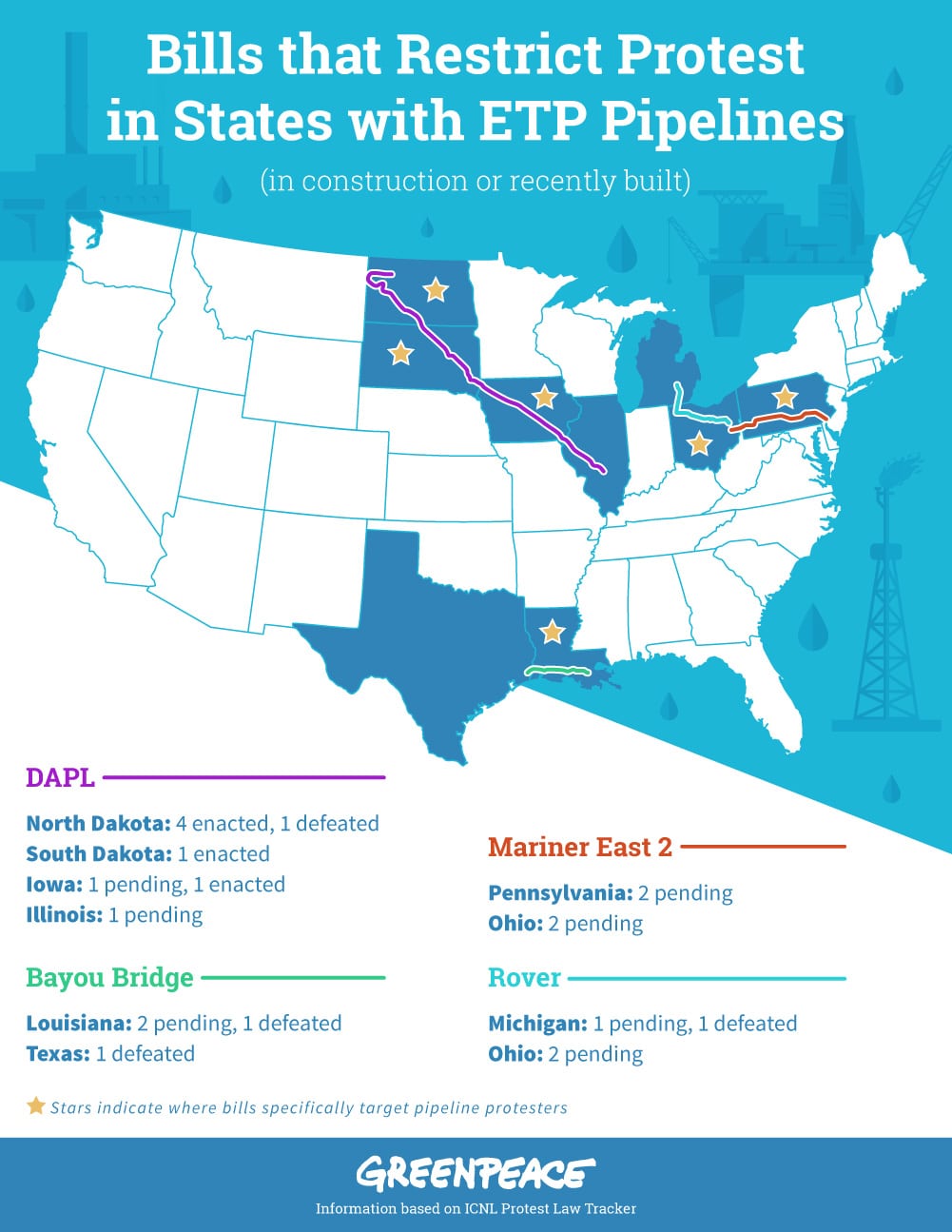

Rise of Anti-Protest Bills

- Following the controversy around the Dakota Access Pipeline, a series of more than 60 bills[9] was introduced across the country restricting the right to protest and criminalizing protest, potentially deterring First Amendment-protected free speech activity.[10] See the section entitled “Tactic 3: Criminalizing Protest with Unjust Laws” for a detailed look at these new proposed bills.

- ETP has directly supported[11] at least one bill (in Iowa) through in-state lobbying efforts. It has likely influenced and/or supported some of these efforts through financial campaign contributions, a network of revolving-door lobbyists and government insiders, and its connection with the American Legislative Exchange Council.[12] For more information about ETP’s link to these lobbying efforts, see the subsection “ETP, ALEC, and Anti-Protest bills.”

Concerns with Private Security Contractors

- ETP continues to work with private security companies, including TigerSwan, which used excessive force and military-style counterterrorism measures against Water Protectors[13] and operated without a license during the events at Standing Rock.[14] See the section called “Tactic 4: Enabling Violence Against Communities” for additional information.

The activities of private security employees during that time raise questions about the level of due diligence exercised by ETP and its contractors, including TigerSwan, in assessing the suitability and providing oversight of persons hired for these situations.[15] - Despite numerous controversies and criticism of TigerSwan’s operation and behavior, ETP continues to have ties with TigerSwan, which provides services on projects in other states, like the Mariner East 2 pipeline project in Pennsylvania.[16] For additional information, see the subsection entitled “TigerSwan in Other States.”

Seizing Private Property

- ETP and related companies are aggressively seizing private property through eminent domain proceedings in all of their current major pipeline projects — Bayou Bridge, Bakken (DAPL, ETCO), ME2, and the Rover Pipeline.[17]

- Private landowners are challenging the legality of the property seizure.[18] For additional information refer to the section “Tactic 5: Seizing Private Property” in the full report.

Spills, Fines, and Safety Concerns

- Pipelines operated by ETP and its related company, Sunoco, and their subsidiaries, spilled hazardous liquids 527 times from 2002 to the end of 2017 — an average of one incident every 11 days.[19]

- Sixty-seven of the spills were reported to have contaminated water, including 18 incidents that contaminated groundwater, and more than 100 of the incidents involved 50 barrels or more. The spills caused an estimated $115 million in property damage.[20]

- ETP has been subject to hundreds of enforcement actions and fined more than $355 million since 2000.[21] See the section called “Dirty Pipelines: Spills and Safety Concerns” for additional information.

ETP’s unwillingness or inability to learn the necessary lessons from DAPL should raise concerns among the company’s institutional financiers, who continue to be exposed to the reputational and financial impacts of ETP’s unacceptable practices.

Therefore, and in light of ETP’s ongoing approach to human rights and its poor record on pipeline spills and safety, banks should end any current financial relationship with ETP and related companies, and should not provide any further financial services, including loans, to the companies.

Introduction

The $3.78 billion Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) project became notorious as a display of abuses, oversight omissions, and unethical corporate tactics, which led to construction delays and to intense national and international scrutiny and criticism of the project. As events unfolded on the ground at Standing Rock, the behavior of Energy Transfer Partners, L.P. (ETP), the company behind the pipeline, attracted global attention to the story of individuals standing up to the company and opposing DAPL as a serious environmental and financial risk.

Although DAPL construction was completed in 2017 and the pipeline is currently in operation, the controversy around the project will have lasting repercussions. Despite the international criticism following the events at Standing Rock, and efforts made by financial institutions, international agencies, and others to evaluate and investigate the issues that arose around DAPL, ETP largely refuses to address and remedy many of its corporate failures. Instead, the company is attributing blame to pipeline opponents and is choosing to instigate legal actions intended to suppress peaceful protests. Worryingly for ETP’s shareholders and funders, this report shows that in its other pipeline projects ETP is engaging in the same corporate behavior and employing many of the same tactics that directly contributed to the controversy at Standing Rock. ETP’s continuing use of these intimidation tactics means that the company and its financial backers risk facing similar controversies in the near future.

“Too Far Too Often” is written for financial institutions investing in and/or lending to ETP and related companies. It details the tactics that ETP employed in its handling of DAPL, and highlights how the company continues to employ these unacceptable practices on other projects. In that context, we recommend that financial institutions should end any current financial relationship with ETP and related companies and should not provide any financial services, including loans, to such companies in the future.

Tactic 1: Violating Indigenous Sovereignty and Rights

Throughout the DAPL permitting and construction process, ETP and regulators faced repeated criticism and legal challenges for failure to follow due diligence in their consultation with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, and failure to respect sovereign rights. Significantly, the project was undertaken without the international standards of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of the Indigenous community.[22]

The Pipeline Route

The Dakota Access Pipeline begins near the border with Canada in northwest North Dakota in the Bakken shale oil fields, and runs underground 1,172 miles through South Dakota and Iowa to an oil storage and transport depot near Patoka, Illinois. Early plans in 2014 involved routing the pipeline across the Missouri River about ten miles north of the city of Bismarck, North Dakota. But when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (whose eventual approval was required for critical parts of the pipeline route) evaluated that routing option, it concluded that it was not viable for several reasons, including the potential threat the pipeline would pose to municipal water supplies in Bismarck,[23] which has a largely non-Indigenous population.[24]

Later in 2014 before submitting the project application to the North Dakota Public Service Commission for necessary approval, the ETP subsidiary Dakota Access, LLC, itself changed the proposed pipeline route.[25] Instead of crossing the Missouri River north of Bismarck, the pipeline would cross the river a half-mile north of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation.

Although the pipeline does not go directly through the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, it crosses through historic unceded treaty lands recognized as belonging to the Great Sioux Nation, including the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, as part of the Fort Laramie Treaties of 1851 and 1868. Historically the U.S. government and corporations have followed a pattern of breaching Treaty agreements, and the DAPL process was no exception.[26]

The routing change meant direct impacts on Indigenous communities, and potential violations of their land and water rights. The route takes the pipeline across the Missouri River upriver of the Tribe’s water intakes, and runs 100 feet under the Lake Oahe reservoir — the primary source of drinking water for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.[27] A pipeline spill could leave the Tribe with limited or no access to potable water.[28]

The pipeline route area through the Treaty land also includes “numerous documented sacred sites and burial grounds, and serves as the source of subsistence, food, water, medicine, culture, religion, and life for tens of thousands of indigenous people.”[29]

No “Free Prior and Informed Consent”

Increasingly in recent years, international norms and laws have evolved to protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples — including their right to give or withhold “free, prior, and informed consent” (FPIC) to development projects that impact their land, health, or cultures.[30] The 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples upholds this FPIC right: “States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them.”[31] In addition, “a variety of non-legal but influential sources, such as the lending policies of multilateral banks and multi-stakeholder codes of conduct, have articulated the expectation that companies obtain FPIC.”[32]

FPIC was not obtained for the DAPL project according to UN standards. In July 2016, the Standing Rock Tribe sued the Army Corps of Engineers for alleged violations of various statutes and, later, the Treaty of Fort Laramie, maintaining that, “The construction and operation of the pipeline, as authorized by the Corps, threatens the Tribe’s environmental and economic well-being, and would damage and destroy sites of great historic, religious, and cultural significance to the Tribe.”[33]

The lawsuit, filed in federal district court in Washington, D.C., claimed that in issuing the permit for the project, the Corps violated multiple environmental and historic preservation statutes; the suit focused on the decision to reroute the pipeline to the area near the Standing Rock reservation without adequate environmental analysis and consultation with the Tribe.[34] In August 2016, the Tribe asked the court for a preliminary injunction to rescind permitting of the pipeline while the lawsuit could be decided.[35]

In September 2016, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, called for a halt to construction on the pipeline, saying, “The tribe was denied access to information and excluded from consultations at the planning stage of the project and environmental assessments failed to disclose the presence and proximity of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation.”[36]

Later, in a full report in September 2017 about the impacts of energy development projects on Indigenous Tribes in the United States, the UN Special Rapporteur dedicated a section to the Dakota Access Pipeline, and concluded:[37]

- The Army Corps of Engineers environmental assessment of the project, required by the National Environmental Policy Act, “failed to identify or address the concerns of the Indian tribes located directly downstream of the pipeline. Maps in the draft assessment initially omitted the reservation or the fact that the pipeline would cross the historic treaty lands of a number of tribal nations.”

- Although the Army Corps of Engineers said it held “numerous consultations” with the Tribes, the Corps confirmed that despite “attempts to contact affected Indian tribes, it was unable to hold the required consultations with them.”

- The affected Tribes, including the Standing Rock Sioux, explained that, “in their view, the attempted contacts were not made sufficiently early in the process but rather after the decisions regarding various aspects of the pipeline had been made, including its route, with limited consideration for sacred sites or the potential impact to their drinking water.”

Water Protectors

The hundreds of Tribes and Indigenous Nations gathered at Standing Rock represented the largest gathering of Indigenous Peoples in recent history. The gathering initially formed near the pipeline at Iŋyaŋ Wakháŋagapi Othí, translated as Sacred Stone Camp, and as the protests grew, additional camps formed, such as Red Warrior Camp and Oceti Sakowin Camp. The motto of Sacred Stone Camp, “Water is Life,” became a rallying cry for a movement that called themselves Water Protectors, rather than protesters. Dallas Goldtooth, an organizer with the Indigenous Environmental Network, explains that the word protest has a negative connotation that makes Indigenous People seem angry or violent.[38] Early on and throughout the resistance to the pipeline, Indigenous Peoples at Standing Rock requested that media refer to them as Water Protectors and briefed press on that preference.[39]

The camps themselves formed the base for many attempts to stop DAPL, but they were also dedicated to the preservation of “Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota cultural traditions,” according to the Sacred Stone Camp website.[40] Lewis Grassrope, a former police officer who had earlier dropped out of the campaign for Tribe Chairman of the Lower Brule Sioux in South Dakota in order to join the Water Protector camps, stayed on even as winter settled in. “What needs to be accomplished hasn’t been,” he said. “We need to stop the pipeline completely, and we need to rebuild our nation and re-establish our ancestral ways.”[41] At this point, the dissent against the pipeline and the purpose of the camps had grown beyond simply a pipeline protest.

To reflect that many of the Indigenous Peoples who camped at Standing Rock focused on prayer and community building, while others engaged in peaceful protest to stop the building of the pipeline, throughout this report we call the Indigenous Peoples who came together at the camps Water Protectors, and specify “protesters” only in referring to specific incidents directly opposing the pipeline.

Violations of Cultural and Human Rights

On-the-ground, Indigenous-led oppositional spirit camps near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation emerged in the spring and summer of 2016.[42] The number of Water Protectors and allies grew significantly over the summer and into the fall of 2016. The historic gathering in opposition to the pipeline brought together some 200 Tribes that had not united in more than 150 years,[43] and gained national and global support and solidarity.

In early September 2016, with the court decision on the injunction still pending, Dakota Access bulldozed an area of the pipeline corridor filled with Tribal sacred sites and burials. As detailed in further depth later in this report, security officers used pepper spray and attack dogs against Water Protectors in the area.[44]

On September 9, the court denied the Tribe’s motion for a preliminary injunction to block the pipeline construction. Minutes later, the U.S. Department of Justice, the Department of the Army, and the Department of the Interior under the Obama Administration announced in a joint statement that because of “important issues raised by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and other tribal nations and their members regarding the Dakota Access pipeline specifically, and pipeline-related decision-making generally,” the Army Corps would not authorize the pipeline construction around and under Lake Oahe “until it can determine whether it will need to reconsider any of its previous decisions regarding the Lake Oahe site under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) or other federal laws. Therefore, construction of the pipeline on Army Corps land bordering or under Lake Oahe will not go forward at this time.”

The statement called on Dakota Access to voluntarily pause all construction activity within 20 miles east or west of Lake Oahe.

Dakota Access did not halt construction. The camps remained, and the violence against the Water Protectors continued. In October, the legal-government sequence was repeated: the court, after issuing a temporary halt in construction in September,[45] again rejected an injunction pending appeal, and the Departments of Justice, Interior, and the Army again urged Dakota Access to voluntarily halt construction around the site, indicating that they were not going to issue the permit needed to cross the Missouri.[46]

Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman Dave Archambault invited Chief Edward John, an Expert Member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, to visit the protest camps “to see, firsthand, the conditions that he, his peoples and those from other communities have been facing in relation to the clearing of the right of way and subsequent construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline.”[47] Chief John released his report on November 1, 2016, finding that:[48]

- “Regardless of both domestic and international law in favor of the Standing Rock Sioux, the pipeline construction has already damaged the security and integrity of the Standing Rock Sioux and the many others that have come to stand in solidarity with people of the Great Sioux Nation. Specifically, the owners and investors have in fact destroyed archaeological, historical and sacred sites of the Sioux.”

- “Construction on the right of way is now proceeding on a 24-hour work day basis, seven days a week. The construction is visible from the ‘south camp’ as equipment is literally bulldozing their way to the Missouri River/Lake Oahe. I was informed that the pipeline company has not received approval to drill on the shores of and under the Missouri River/Lake Oahe. Given that there are no approvals or authorizations in place, it is a significant expense and exposure for the company to proceed with the work.”

- “…it is clear to me that the project has and will adversely impact the Standing Rock Sioux and their waters specifically, as well as cultural, spiritual, sacred and ancient village sites on their lands in their territory.”

- “I am advised by a Sioux elder and cultural leader that so far some 380 cultural and sacred sites along the pipeline route have been destroyed by work associated with the right of way clearing for the pipeline.”

In December 2016, the Army Corps of Engineers halted construction on the pipeline and stated that it would conduct a full environmental review of the pipeline’s impacts before granting the final easement to allow it to cross Lake Oahe. But in February 2017, within days of taking office, newly elected U.S. President Donald Trump ordered an expedited review and approval to allow the pipeline construction to be completed.

In response, Amnesty International USA (AIUSA) issued a statement saying that DAPL construction should not resume until the environmental impact review was completed and the Tribe’s consent was sought. AIUSA condemned the resumption of pipeline construction: “This is an unlawful and appalling violation of human rights. The United States is obligated under international law to respect the rights of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and all other Indigenous Peoples. To allow this pipeline to go forward without sufficient assessment of how it will impact their land, culture, and access to clean water is a violation of their rights and sovereignty of their land.”[49]

Repercussions in the Financial Community

The overall handling of DAPL was so egregious that the lead financial underwriter for the DAPL project loan, Citibank, engaged with Energy Transfer Partners “to discuss our concerns and advocate for constructive dialogue with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in an effort to come to a resolution.”[50] A consortium of banks that had participated in the DAPL project loan hired an outside firm, Foley Hoag LLP, to conduct an independent assessment to include the evaluation of “policies and procedures employed by the project’s sponsors, Energy Transfer Partners and Sunoco Logistics, in the areas of security, human rights, community engagement and cultural heritage.”[51]

Although Foley Hoag’s report was not made public, the public summary of the report confirmed that FPIC is critical to “international industry good practice”: “The report’s analysis draws extensively on the International Finance Corporation’s Environmental and Social Performance Standards (“IFC Performance Standards”), particularly the provisions stemming from the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. These standards are a widely respected benchmark for good practice with regard to community engagement, including company consultation with Indigenous Peoples and security practices.”[52]

In May 2017, a group of ten European banks wrote to the Secretariat of the Equator Principles Association expressing alarm over shortcomings in the applied due diligence around FPIC, stating that “In addition to the reputation damage that this has caused to the banks involved [in the project], we believe that this is likely to damage the reputation of the Equator Principles (EPs) as a ‘golden standard’ and a common playing field for determining, assessing and managing environmental and social risks in projects.”[53]

The Equator Principles are a policy framework that establishes a minimum benchmark for socially and environmentally responsible lending. Ninety-two banks have adopted the Equator Principles, several of which were on the project loan for DAPL. To date, there has been a loophole for “designated countries” such as the United States; the assumption has been that there are strong U.S. federal laws around Indigenous rights and FPIC, and that therefore the same amount of due diligence isn’t needed by banks participating in projects in the United States.[54] Standing Rock proved that wrong — in fact demonstrating that U.S. law and how it was interpreted and executed with regards to DAPL was not up to the standards and best practices expressed in the spirit of the Equator Principles.

In fall 2017, the Equator Principles Association convened and committed to a process of updating the Equator Principles over the course of 18 months, addressing challenges “including application of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) in different jurisdictions, the ‘Designated Countries’ approach within the EPs, climate risk…”[55]

Ahead of that meeting, Greenpeace International, BankTrack and more than 60 other international environmental organizations had already called for a formal process of revising the Equator Principles, citing DAPL as an example of their failure:[56]

“… instead of preventing non-financial and financial risk for banks, and preserving the only source of drinking water for the Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribes, the current EP framework allowed for the project to proceed in a violation of the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) that has been recognised even by banks financing the project. The DAPL project also resulted in substantial losses for several of the EP banks involved, and dealt a severe blow to the reputation of the EP initiative as a robust risk management framework. DAPL was only the latest in a long line of projects affecting Indigenous Peoples’ lands that have been considered fully compliant with the Equator Principles — despite devastating impacts on Indigenous communities.”

Tactic 2: Silencing Free Speech with Intimidation

As the Water Protectors’ opposition to the pipeline construction increased and received increased attention, ETP’s tactics, in conjunction with local law enforcement, became more aggressive. ETP’s consistent and unrelenting response to DAPL opposition has been to try to quash legitimate dissent with intimidation, violence, arrests, and lawsuits.

Arbitrary Arrests

Open Democracy reported in December 2016 that security firms hired by ETP and local and state police agencies were routinely using “excessive force, arbitrary arrest and intimidation tactics to subvert the protesters constitutional and international rights to expression and peaceful assembly.”[57] In the course of one month, more than 400 Water Protectors were arrested, “many of whom have been subjected to highly-questionable charges including engaging in riots and conspiracy to endanger by fire and explosion.”[58]

In a letter calling on the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate the actions of law enforcement agencies at the Standing Rock site, Amnesty International cited the arrests of at least 140 people in a single day in October 2016: “Reports from legal aid support based at the protest camp are that all individuals arrested were required to pay bail, even for minor offenses such as trespassing, and were all strip searched upon processing.”[59]

In November 2016, a United Nations expert on human rights called on ETP to pause construction activity near Lake Oahe, pointing to “local security forces employing an increasingly militarized response to protests.” The UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights reported, “Law enforcement officials, private security firms and the North Dakota National Guard have used unjustified force to deal with opponents of the Dakota Access pipeline, according to Maina Kiai, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.”[60] “Mr. Kiai also said an announcement on 8 November by pipeline operator Energy Transfer LLC Corporation, stating that the final phase of construction would start in two weeks, ‘willfully’ ignored an earlier public statement by federal agencies.” Mr. Kiai said that he was concerned at the “scale of arrests and the conditions in which people were being held”: “Marking people with numbers and detaining them in overcrowded cages, on the bare concrete floor, without being provided with medical care, amounts to inhuman and degrading treatment.’”[61] In this report and other accounts, it is not always clear which acts were performed by private security and which by police, and what role private security had in instigating the police to those actions. This report seeks to highlight the interconnected nature of private security actions with local law enforcement at the Standing Rock Protests.

“This is a troubling response to people who are taking action to protect natural resources and ancestral territory in the face of profit-seeking activity,” Mr. Kaia said. “The excessive use of State security apparatus to suppress protest against corporate activities that are alleged to violate human rights is wrong and contrary to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.”[62] His call for ETP to halt construction activity was endorsed by six additional UN experts on human rights and the rights of Indigenous Peoples.[63]

As of April 2018, 253 of the 831[64] state arrests from Standing Rock were still open, according to the Water Protector Legal Collective (WPLC). Nineteen were convicted at trial (three of those are being appealed to the State Supreme Court), and 337 were either dismissed or acquitted at trial.

In an attitudinal survey, the WPLC found that 75 percent of Morton County respondents and 77 percent of Burleigh County respondents had already prejudged protesters as guilty.[65] This information was submitted to request a change of venue in cases of notable defendants like Red Fawn Fallis and Michael “Little Feather” Giron. In both cases, the change of venue was denied, and like 224 others, Fallis and Giron both reached plea agreements. Fallis reached a plea agreement for two felonies and is awaiting sentencing, which could be from 21 to 57 months in prison.[66] Giron was sentenced to 36 months in prison.

In one case, a judge sentenced two Water Protectors even though the prosecution was not asking for jail time.[67] The number of arrests, combined with the court system’s inability to handle that volume, meant that many cases were delayed far longer than is typical, including nearly 200 cases that were abruptly rescheduled by court officials via unsigned emailed notice in January 2017.[68]

Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation

In August 2016, ETP’s subsidiary Dakota Access LLC sued Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman Dave Archambault II, Standing Rock Councilman Dana Yellow Fat, and several other named and unnamed defendants, seeking “restraining orders and unspecified monetary damages.” The suit was an attempt by the company to prevent Water Protectors from protesting near the pipeline and to make them pay damages to the company for past protests.[69]

The court initially granted a temporary injunction before Chairman Archambault and the others had a chance to respond[70] — a restraining order that would have meant that they could be held in contempt of court if they demonstrated or engaged in religious expression near the pipeline route.[71] The order was lifted a month later, and in May 2017 the ETP lawsuit was dismissed altogether.

The lawsuit against the Water Protectors has all the markings of a “Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation” (SLAPP), a meritless suit meant to silence free speech through expensive and time-consuming litigation. The use of SLAPPs to shut down free speech is increasingly recognized as a violation of human rights. A 2016 report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders stated, “Legal forums are increasingly being used to silence defenders, particularly those who oppose large-scale development projects and the actions of companies. The use of strategic litigation against public participation lawsuits silences defenders, effectively denying them their rights to freedom of expression and participation in public affairs. Defenders require support in their defence against such lawsuits, the financial and psychological burdens of which are often so great that they distract and demobilize defenders.”[72]

Recognizing the threat that SLAPP suits pose to free speech and human rights, a number of U.S. states have passed anti-SLAPP laws that limit the use of SLAPPs to varying degrees. The Public Participation Project, which documents and campaigns for anti-SLAPP laws and works to keep them from being gutted, argues that, “SLAPPs are used to silence and harass critics by forcing them to spend money to defend these baseless suits. SLAPP filers don’t go to court to seek justice. Rather, SLAPPS are intended to intimidate those who disagree with them or their activities by draining the target’s financial resources. SLAPPs are effective because even a meritless lawsuit can take years and many thousands of dollars to defend. To end or prevent a SLAPP, those who speak out on issues of public interest frequently agree to muzzle themselves, apologize, or ‘correct’ statements.”[73]

North Dakota has no anti-SLAPP legislation.

In August 2017, after the pipeline was complete, ETP continued its use of SLAPP suits for intimidation, filing a $900 million lawsuit against Greenpeace entities, Banktrack, and the movement, EarthFirst!, accusing the organizations of inciting and directing acts of “eco-terrorism.”[74] The suit was brought under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), a law enacted in 1970 that was initially designed to tackle mafia activity.[75] The use of RICO to treat advocacy activity as inherently criminal poses a serious threat to free speech and advocacy. The UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly has described RICO suits as “a worrying new approach” being misused “to intimidate advocacy groups and activists by enabling corporations to smear these groups as ‘criminal enterprises’, while claiming exorbitant damages (RICO entitles plaintiffs to claim treble damages as a punitive measure) for the ‘harm’ they claim to have suffered.”[76]

In a 2017 interview, ETP CEO Kelcy Warren said “Could we get some monetary damages out of this thing, and probably will we? Yeah, sure. Is that my primary objective? Absolutely not. It’s to send a message, you can’t do this, this is unlawful and it’s not going to be tolerated in the United States.”[77]

A Larger Pattern of Intimidation

The arbitrary arrests and anti-free-speech lawsuits are not isolated incidents of corporate intimidation tactics; however, the use of RICO and the high damages set the lawsuit apart from the rest, and could further embolden oil and pipeline companies to take this kind of action.

- In March 2018, Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC (TM), a subsidiary of Kinder Morgan Canada, which faced overwhelming opposition in its controversial expansion of the Trans Mountain pipeline in British Columbia, sued 15 individual activists and “persons unknown,” seeking a permanent and interim injunction as well as damages, interest, and costs. The complaint claimed as a legal basis nuisance, conspiracy, and unlawful interference with economic relations.

- In April 2018, Mountain Valley Pipeline sued tree-sitter protesters who had stationed themselves in trees being cut along the pipeline route. The company sued Theresa “Red” Terry and her daughter, Theresa Minor Terry, for civil contempt, and asked a federal court to fine them for every day of violation, to direct U.S. marshals to remove the tree-sitters, and to charge them for damages from the pipeline construction delay. The women climbed down from the trees in early May 2018.[78]

- In October 2014, TM sued five protesters, the pipeline-opponent group BROKE, and “persons unknown” after protests against its pipeline-expansion study work in a national park on Burnaby Mountain. The company sought damages it estimated at more than $5 million per month of delay, as well as injunctive relief, on the basis of trespass, assault, intimidation, nuisance, inducing breach of contract and conspiracy. The lawsuit provoked wide controversy given that the “trespass” allegedly took place in a public park and that the protesters’ facial expressions constituted “assault” (prompting a viral social media campaign of people posting pictures of their “Kinder Morgan face”). In January 2015 TM dropped the case.

- Vancouver-based Stand.earth was ordered to pay Enbridge, Inc.’s court fees totaling $14,500 after Stand.earth lost a 2014 court case against the proposed expansion of Enbridge’s Line 9 pipeline. The organization refused to pay the court as a “point of principle,” and in October 2017, sheriffs arrived at the Stand.earth office to seize assets from the organization. The sheriffs filmed the office and told staff that they were not allowed to remove any of the items, and then left, saying they would be back with a moving track. Amid a social media backlash, Enbridge backtracked almost immediately, cancelling the seizure in a pair of tweets three hours later. Stand.earth Canada director Karen Mahon said, “Enbridge made $4.6 billion last year. This is not about the money. This is an attempt to intimidate us from taking action on behalf of the climate and the public.”[79]

- After ETP filed its 2017 SLAPP / RICO lawsuit against Greenpeace entities and others, “litigation hold letters” were sent to numerous non-parties, even though — as non-parties — they had no obligation to preserve relevant documents. These letters were sent to a number of Indigenous groups as well as independent Greenpeace offices outside the United States and organizations not named in the lawsuit.

Tactic 3: Criminalizing Protest with Unjust Laws

Following the controversy around the Dakota Access Pipeline, a series of more than 60 bills was introduced restricting the right to protest and criminalizing protest. As of the publication of this report, nine have passed and 26 are pending; three of those nine bills that have passed are in North Dakota, the heart of the DAPL controversy. The oil industry in general, ETP, and the American Legislative Exchange Council each had a role in popularizing these bills and spreading this legislative tactic, which is having a long-term chilling effect on free speech, especially around protests against pipelines.

Even just introducing these protest bills has the potential to chill speech and deter First Amendment protected activities. UN experts on freedom of expression and assembly, David Kaye and Maina Kiai, expressed concerns about the new influx of anti-protest bills following the DAPL protests: “The Bills would have a chilling effect on protestors, stripping the voice of the most marginalized, who often find in the right to assemble the only alternative to express their opinions. We are particularly concerned about the fact that several Bills directly target environmental activists… these Bills were reportedly proposed as a response to the protests organized by activists and opponents of the Dakota Access Pipeline in North Dakota.”[80]

The American Legislative Exchange Council: Methods and Funding

The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) has played a significant role in introducing and popularizing bills that criminalize protest, especially concerning “critical infrastructure.” ALEC is a controversial organization that avoids lobbying disclosure requirements by bringing state lawmakers and corporate lobbyists together in private meetings where they collaborate on so-called “model bills” for state legislatures.[81]

ALEC’s most prominent and longstanding corporate members include fossil fuel companies Koch Industries,[82] ExxonMobil,[83] and Peabody Energy,[84] all of which have financed and helped manage ALEC operations for decades.

Only 2 percent of ALEC’s funding comes from legislative dues; the other 98 percent comes from private donations through a variety of streams, including oil companies and trade groups like the American Petroleum Institute (API).[85] Despite playing an active role in creating legislation for state lawmakers, ALEC funding does not require public disclosure.

ALEC’s Role In Promoting Anti-Protest Bills

In early 2017, during the final months of the protests at Standing Rock, oil companies turned to ALEC-backed legislators to introduce anti-protest bills in several states. These bills seek to increase criminal penalties for people planning or conducting a wide variety of protest on private property, or protests concerning so-called “critical infrastructure.”

The first of these “critical infrastructure” bills was authored by Oklahoma Representative Charles McCall,[86] a registered member of ALEC,[87] and introduced in February 2017. According to ALEC, it then inspired a model bill called the Critical Infrastructure Protection Act.[88]

The bills became law in North Dakota, Oklahoma,[89] and South Dakota.[90] Similar bills were introduced in Georgia, Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, and Pennsylvania.

Even though DAPL construction through South Dakota was already complete, the governor’s office said that passage of the law there was an “important proactive step toward reducing potential disruption from protests when construction on the Keystone XL pipeline begins in the state.”[91] The South Dakota law allows the governor to set up “public safety zones” in which protest activities can be limited to gatherings of 20 people or less — a measure that prompted Remi Bald Eagle, who works in intergovernmental affairs with the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, to warn that the law “comes dangerously close to restricting constitutional rights. Nowhere in the constitution did it say anything about how many people can assemble peaceably.”[92]

The oil industry’s anti-protest push continued in 2018. ALEC members in the Iowa state house helped pass a law[93] very similar to the ALEC template bill.[94] Wyoming’s legislature passed a version that was ultimately vetoed by Governor Matt Mead because the proposed criminal punishments were “imprecisely crafted” and redundant with existing law.[95] Dozens of anti-protest bills, such as those relating to “critical infrastructure” or heightened trespassing penalties, are still being considered by legislators in several states, including Minnesota, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.[96]

ETP, ALEC, and Anti-Protest bills

Tracking the funding to ALEC, lobbying, and campaign contributions reveals connections between Energy Transfer Partners and ALEC as well as ETP’’s own role in popularizing and spreading this tactic this tactic.

While it is not possible to know the full involvement of ETP with ALEC because funding ALEC does not require public disclosure, it is known that ETP spent $10,000 in 2010 for a Director level sponsorship of ALEC’s Annual Conference,[97] and was a “Trustee” level sponsor of the 2014 Conference,[98] buying time with lawmakers.

In addition, Iowa State lobbying disclosures show that ETP directly advocated for the legislation in Iowa along with Koch Industries and the American Petroleum Institute.[99] One of ETP’s two listed lobbyists on the bill, Jeff Boeyink, has been associated with[100] ALEC in his capacity as an Iowa anti-tax lobbyist. In testifying before the Senate Subcommittee, Boeyink pointed out the “huge monetary implications” of protest for ETP. John Benson, a legislative liaison for the Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, said that “operators of these facilities want criminal charges that are appropriate for such actions.”[101]

While Iowa’s lobbying disclosures show activity on specific bills, other states only require lobbyists to be registered but do not show activity on specific legislation. However, Energy Transfer Equity, the parent company of ETP, spent $1.4 million on lobbying in the U.S. in 2016, at the peak of the resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline,[102] compared to just $240,000 in 2009.

From 2015 to 2018, ETP had two registered lobbyists in North Dakota: Joel Gilbertson (who was the ALEC state chairman in 2014[103]) and Levi Andrist (grandson[104] of former Senator John Andrist, who was a member of ALEC[105]), but had no lobbyists registered in North Dakota in 2014, before the controversy.

Currently, there are two other anti-protest bills pending in Pennsylvania[106] — where ETP’s Mariner East 2 natural gas pipeline is currently under construction — and one in Ohio[107] where the Rover gas pipeline is under construction. In both states bills have been proposed that seek to increase penalties for protests that hinder the functions of critical infrastructure facilities; the Ohio bill would even criminalize the flying of a drone over such a facility. ETP lobbyists are registered in both states.[108]

Energy Transfer Partners contributed to the campaigns of 35 candidates for the House and Senate in Pennsylvania, as well as to the campaign of Tom Wolf, the current Governor, for a total of $27,500. Additionally, in the 2016 cycle, ETP made a donation to Mike Regan, the sponsor of the Pennsylvania bill.[109]

The pattern of how and where these bills have been introduced, as well as ETP’s spending pattern on lobbying and campaign contributions, could imply that its role in promoting and lobbying for these bills is significant. Additionally, Kelcy Warren’s own rhetoric around pipeline protesters demonstrates his own attitude regarding protest; he refers to social media about bank funding of pipelines as “terrorism”[110] in one interview, and says on a panel discussion that protesters should be “removed from the gene pool.”[111]

The Impact of Anti-protest Bills

The three bills criminalizing protest in North Dakota that passed in 2017 were known informally as the DAPL protest bills.[112] These newly enacted laws significantly increase penalties for already illegal conduct such as rioting and incitement to riot (a charge that implicates speech),[113] and for criminal trespass.[114] Another of the three laws creates a year-long jail sentence for anyone wearing a face covering, including a hood, while committing a crime.[115] One proposed bill would give impunity to any driver who hit or even killed a protester with their car as long as it was deemed unintentional,[116] an idea that was widely criticized as appearing to encourage violence against protesters.[117] Similar bills have been introduced in six other states, but so far none have been enacted.

The legislative trend sparked by the DAPL protests shows no signs of slowing down, and the resulting impact could have disastrous consequences on First Amendment rights and free speech — consequences extending far beyond pipelines. Noting the trend of these anti-protest bills in protest hotspots, the American Civil Liberties Union wrote, “Legislators in states with robust protest activity should have one priority: listening to those voices (even if, and perhaps especially when, they disagree with them). Sadly, we’re seeing a different trend — one that tries to silence them. In a year of historic activism, that response isn’t just unconstitutional: It’s fundamentally un-American.”

Tactic 4: Enabling Violence Against Communities

As Indigenous opposition to DAPL grew in the summer and fall of 2016, ETP private security and federal, state, and local law enforcement resorted to surveillance and increasingly militaristic tactics against Water Protectors and allies, tactics which were revealed when The Intercept published a large cache of leaked documents in a series of articles.

The police were said to target protesters “with worrying frequency” using rubber bullets, pepper spray and attack dogs.[118] In 2017, the ACLU described how “All eyes were on Standing Rock late last year as unwarranted armored vehicles rolled in. Law enforcement used automatic rifles, sound cannons, and concussion grenades against water protectors… Personnel and equipment pouring in from over 75 law enforcement agencies from around the country and National Guard troops created a battlefield-like atmosphere at Standing Rock. Escalated police militarization was used to intimidate and silence water protectors’ free speech and their right to protest a pipeline which passes near sovereign territory… With resilience, water protectors have already endured militarized crackdowns, police abuse, and daily intimidation — simply for defending their water rights.”[119]

On Labor Day weekend in 2016, Democracy Now! captured video footage of ETP private security guards using attack dogs and pepper spray against demonstrators. The video was viewed 14 million times on social media, and was picked up by major media outlets.[120] Days later, the North Dakota Bureau of Criminal Investigation issued an arrest warrant for Democracy Now! host Amy Goodman, on charges of engaging in a riot[121] — charges that were later dropped.[122]

Chief Edward John, the Expert Member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues who visited the pipeline site in late October 2016, reported that, “I was repeatedly told of constant aerial surveillance by drones, airplanes and helicopters and on-the-ground surveillance by officers in vehicles stationed on high points of land adjacent to the south camp. While on site some Standing Rock members pointed out several law enforcement vehicles parked on a nearby hill that is known by tribal members as a burial site. This together with the presence of significant levels of ‘security’ forces from local police, neighboring state police forces, DAPL private company security contractors, and the national guard of North Dakota have all contributed to heightened insecurity and intensity…

“All these actions have directly contributed to a ‘war zone’ atmosphere and intensified levels of scrutiny. On the bridge near the south camp I witnessed burned out vehicles stationed to prevent passage either way. Large concrete blocks have also been laid across the bridge beyond the destroyed vehicles. Nearby I met officers in body armor, fully armed and in full camouflage gear.”[123]

TigerSwan

In May 2017 The Intercept released documents that shed light on the security tactics used by law enforcement and security firms hired by ETP. “Police became notorious for their use of so-called less than lethal weapons against demonstrators, including rubber bullets, bean bag pellets, LRAD sound devices, and water cannons,” The Intercept reported. “But it was the brutality of private security officers that first provoked widespread outrage concerning the pipeline project.”[124]

The documents included leaked internal communications from TigerSwan, a private security and intelligence contractor based in Apex, North Carolina. TigerSwan was founded at the height of the Iraq War by retired U.S. Army Col. James Reese, who had been assigned to the Army’s special forces Delta unit. TigerSwan has approximately 350 employees, and offices in Iraq, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, India, Latin America, and Japan.[125] TigerSwan says it achieves results with what it calls “world class methods” registered as F3AR®, NIFE®, and “Guardian Angel,” and its “mantra” is “Solutions to Uncertainty.”®[126]

In fall 2016, after the Democracy Now! video release showing other ETP security using attack dogs and pepper spray against Water Protectors, ETP hired TigerSwan as a contractor on DAPL. In its role, TigerSwan managed other security contractors on the project, which included Silverton, Russell Group of Texas, 10 Code LLC, Per Mar, SRC, OnPoint, and Leighton.[127]

Despite the backlash to the violent tactics, TigerSwan and the contractors they managed continued to use brutal tactics with Water Protectors and allies at Standing Rock. “TigerSwan targeted the movement opposed to the Dakota Access Pipeline with military-style counterterrorism measures, collaborating closely with police in at least five states,” The Intercept noted. “Internal TigerSwan communications describe the movement as ‘an ideologically driven insurgency with a strong religious component’ and compare the anti-pipeline water protectors to jihadist fighters.”[128] Among documents that The Intercept obtained through public records requests were “daily intelligence updates” that TigerSwan developed and shared with law enforcement officials, “contributing to a broad public-private intelligence dragnet.”[129] Documents obtained by The Intercept included daily “detailed summaries of the previous day’s surveillance targeting pipeline opponents, intelligence on upcoming protests, and information harvested from social media.”[130] They also provide “extensive evidence of aerial surveillance and radio eavesdropping, as well as infiltration of camps and activist circles.”[131]

ETP CEO Kelcy Warren makes no secret of his opinion of protesters. “Warren is certain that his version of the facts should carry the day against protesters,” The Dallas Morning News reported, “including musicians who Warren has worked with for years and a Norwegian bank that is helping finance the pipeline but raised an objection over the weekend to the way ETP has dealt with ‘indigenous people’s rights.’ Warren totally does not buy those arguments. He said the protesters are ignoring reality. The decision of Norway’s DNB bank was a mistake, he said. And other banks are also getting attacked via social media in an effort to cut financing to the energy industry. ‘That’s all that nonsense is,’ he said. ‘It’s just terrorism.’”[132]

On October 27, 2016 hundreds of law enforcement officers (local, federal, and officers from several states) forcibly evicted Water Protectors from one of the camps, Treaty Camp, demolishing the camp and arresting 142 activists. TigerSwan had provided law enforcement with a surveillance briefing the day before the eviction.[133] As the eviction was underway, Kyle Thompson, an employee of Leighton Security — one of the security firms managed by TigerSwan, drove a pickup truck at high speed toward Oceti Sakowin, a larger Water Protector camp. Forced off the road by Water Protectors, Thompson covered his face with sunglasses and a bandana and brandished an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle, at one point pointing the weapon into the faces of the unarmed protesters.[134] Thompson was surrounded by Water Protectors until he could be disarmed and arrested by officers from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Thompson was released without charges.[135]

The activities of private security employees, including Kyle Thompson, raise questions about the level of due diligence exercised by ETP and its contractors in assessing the suitability and providing oversight of persons hired for these situations.

Operating Without a License

On September 23, 2016, the North Dakota Private Investigation and Security Board (PISB) notified TigerSwan that the PSIB was aware that the company was operating in North Dakota without a license, and requested information about TigerSwan’s activities in the state. James Reese applied for a North Dakota private security license five days later.[136]

In correspondence between TigerSwan and the PSIB in the following months, TigerSwan denied that it had engaged in private security activities, referring to its work for ETP instead as “management and IT consulting.” The PISB denied a license to TigerSwan in December 2016, in part because Reese had not disclosed his past arrests — including an arrest in 2015 flagged as domestic violence that was later dismissed[137] — and had not provided sufficient information “for the Board to determine whether a reported offense or adjudication has a direct bearing on Reese’s fitness to serve the public.”[138] Reese requested an administrative review of the license denial, and the license was denied again after a special PISB meeting in January 2017. (At that meeting board members were asked to destroy copies of material relating to TigerSwan and Reese at the close of the meeting.)[139]

In June 2017, the PISB brought a civil suit in North Dakota against TigerSwan for illegal and unlicensed operations during DAPL construction. The suit sought fines and penalties against TigerSwan, and sought to ban TigerSwan from working in the state.[140] PISB held that at the time of the suit, TigerSwan continued to work in North Dakota, maintaining “roving security teams,” that TigerSwan personnel “acting as security personnel are armed with semiautomatic rifles and sidearms while engaging in security services,” and that the company continued to provide private investigative services on behalf of its client, ETP.[141] The complaint also described tactics used by TigerSwan, including “flyover photography,” “surveillance of social media accounts,” placing or attempting to place “undercover private security agents within the protest group,” and coordination with local law enforcement officials.[142]

One of three counts in the PISB civil suit was dismissed in April 2018 and the remaining counts were dismissed in May 2018. The PISB attorney said he plans to file an appeal.[143]

TigerSwan in Other States

Given the incitement of police activity, the intensity of violence directed toward Water Protectors, and the disregard for state regulations that TigerSwan demonstrated in North Dakota, it is concerning that ETP would choose to contract with TigerSwan to provide security services on projects in other states, like the Mariner East 2 pipeline project in Pennsylvania.[144]

In June 2017, TigerSwan applied for a license to operate in Louisiana, where construction is underway on ETP’s Bayou Bridge pipeline. (Additional information on the Bayou Bridge pipeline can be found later in this report.) The application was denied in July 2017. The executive director of the Louisiana State Board of Private Security Examiners cited the North Dakota license denials and litigation in refusing to certify TigerSwan.[145]

Shortly after the license application was denied in Louisiana, TigerSwan employee Lisa Smith registered a new company (LTSA) and applied for a permit for private security, while concealing her TigerSwan employment. Smith’s application was denied, with the state board noting she had “intentionally engaged in material omission of fact.”[146]

In February 2017, retired general James “Spider” Marks wrote a pro-ETP opinion article for the Daily Advertiser in Louisiana, without disclosing his membership on a TigerSwan advisory board.[147][148] In March 2018, James Marks and Washington DC-based public relations and lobbying firm DCI Group used robocalls to invite Louisiana residents to take part in a “free informational conference call on the Bayou Bridge pipeline,” without revealing the associations between ETP, TigerSwan, Marks, and DCI Group,[149] which has ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).[150]

TigerSwan does have license to operate in Pennsylvania, where its tactics of harassing protesters mirror techniques it employed for ETP at DAPL, including monitoring resistance to the controversial Mariner East 2 pipeline (ME2),[151] which is also owned by ETP and related companies. In April 2017, the Mariner East 1 pipeline, which runs parallel to the proposed path of ME2, spilled 20 barrels of ethane and propane near Morgantown, Pennsylvania. “It would be weeks before the public learned of the leak of highly explosive natural gas liquids,” The Intercept reported. “According to a source with direct knowledge of TigerSwan’s operation, making sure nobody found out about the incident was part of TigerSwan’s mission on the project.”[152]

In September 2017, four Pennsylvania residents, including Elise Gerhart, sued ETP, its related company Sunoco Pipeline, and TigerSwan, alleging that the companies had violated the residents’ constitution rights when police arrested them on Gerhart’s property in March 2016. The residents were protesting tree-cutting on an easement on the property that the company obtained through eminent domain to build the pipeline. According to the lawsuit, ETP/Sunoco entered the property almost a year before the final state permits were issued for pipeline construction, and before it was allowed to do so under a “writ of possession” issued by a state judge in April 2017.[153]

In a further example of TigerSwan’s use of misinformation to undermine pipeline opponents’ credibility, according to the lawsuit, TigerSwan and a publicist, Nick Johnson, another co-defendant in the case, falsely claimed on Facebook that Elise Gerhart and the others are “fronts for the Russian government, which is trying to disrupt U.S. energy production because it fears its own share of world energy markets will drop.”[154]

Tactic 5: Seizing Private Property

“The beneficiaries are likely to be those citizens with disproportionate influence and power in the political process, including large corporations and development firms. As for the victims, the government now has license to transfer property from those with fewer resources to those with more. The Founders cannot have intended this perverse result.”—U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, in her dissent in Kelo, et. al. v. City of New London, et al., 545 U.S. 469 (2005).

ETP, Sunoco, and their subsidiaries are aggressively seizing private property through eminent domain proceedings in all of their current major pipeline projects — Bayou Bridge, DAPL, ETCO, ME2, and the Rover Pipeline — in order for ETP to build the pipelines through private property. On behalf of ETP, state governments in seven states (Pennsylvania, Ohio, Iowa, West Virginia, Michigan, North Dakota, Louisiana) are taking hundreds of landowners to court to expropriate their land, claiming that there is a public purpose or benefit.

The companies’ efforts to obtain and maintain easement agreements from property owners have been met with vigorous resistance in several areas, and in some cases, private landowners have filed lawsuits to challenge the property seizure, or at a minimum, to bring transparency to the process.

In some areas, the fact that a pipeline company has acquired an easement to build on private property concerns homeowners. “The [Mariner East] project has unsettled the residential real estate market, as some fearful homeowners sold out ahead of construction, and some buyers moved in unaware of the forthcoming disruption,” The Inquirer reported. “Many who remained are basically stuck until the dust settles, uncertain of the value of their homes.”[155]

Historically, eminent domain proceedings were used by the government to take private land for a public use — for example to build roads — while compensating the owner. The legal standard was expanded to include projects that have a “public purpose,” a definition that has been broadened further to allow the government to take private lands and transfer the rights to private companies. Originally, this was applied to projects that could provide a direct economic benefit to the locality, such as redevelopment to stimulate the local economy, but in cases such as pipeline construction it is being used for projects where there is active debate and no agreement that there is proven benefit to the immediate community.

Iowa: Dakota Access Pipeline

DAPL crosses 343 miles of land in Iowa. ETP and its subsidiary Dakota Access, LLC were not able to get the consent of all the affected landowners to allow the pipeline to cross through their property. The Iowa Utilities Board (IUB) granted Dakota Access the permit to construct the oil pipeline through Iowa in March 2016, and in doing so, gave Dakota Access eminent domain powers in the project. Although the use of eminent domain was deeply unpopular among Iowans,[156] Dakota Access used eminent domain proceedings to seize the private property that landowners did not give up willingly.

A group of landowners, together with the Sierra Club Iowa Chapter, brought a lawsuit against the IUB, arguing that the DAPL permit should not have been granted, and that both Iowa law and the U.S. Constitution preclude the use of eminent domain to condemn property for a crude oil project.[157] In Iowa, a company must show that a pipeline meets the legal standard of providing a “public convenience and necessity” in order get a permit from the IUB.[158] Dakota Access argued that there was an economic value to the public by creating construction jobs, but Sierra Club argued that construction jobs and general economic impact have nothing to do with whether the pipeline will provide a needed service. The Iowa Supreme Court is currently reviewing the case and will likely issue a decision in 2018.

Louisiana: Bayou Bridge Pipeline

ETP’s Bayou Bridge Pipeline (BBP) would transport crude oil cross 162 miles of ecologically sensitive land in Louisiana — passing through 11 parishes, and impacting 700 bodies of water, including many in the Atchafalaya Basin, an environmentally sensitive National Heritage Area. Like DAPL, the BBP project is only possible through the seizure of private lands. ETP has used eminent domain proceedings to expropriate more than 400 pieces of private property in Louisiana.

BBP already faces multiple lawsuits in federal and state courts regarding environmental regulations; in January 2018 three Louisiana organizations, Atchafalaya Basinkeeper, Louisiana Bucket Brigade, and 350 New Orleans, represented by the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), filed suit to obtain public records regarding BBP’s “land grabs.”[159] With BBP asserting that it has “legal authority to exercise eminent domain under state law as a ‘common carrier’ because its proposed pipeline is ‘in the public interest,’” the groups argue that the company should be subjected to the same transparency requirements that would be required of public agencies exercising eminent domain.[160]

CCR had requested BBP records — including records of communications with local, parish, state, and federal agencies, as well as “any records of surveillance or other operations concerning opponents by private security companies such as TigerSwan,”[161] to “ensure the operators of the pipeline are transparent in all their dealings with public officials and landowners,” as the companies develop “public relations efforts in response to local pipeline opposition.”[162]

Dirty Pipelines: Spills and Safety Concerns

Pipelines operated by ETP and its related company, Sunoco, spilled hazardous liquids 527 times from 2002 to the end of 2017 — an average of one incident every 11 days.[163]

Those 527 incidents, reported by the Pipeline Hazardous Material Safety Administration (PHMSA), released a total of 87,273 barrels (3.6 million gallons, or about five-and-a-half Olympic-sized swimming pools) of hazardous liquids, including 66,515 barrels (2.8 million gallons) of crude oil. Sixty-seven of the spills were reported to have contaminated water, including 18 incidents that contaminated groundwater, and more than 100 of the incidents involved 50 barrels or more (2,100 gallons, a volume which is considered “significant” by the federal regulator). The spills caused an estimated $115 million in property damage.[164]

ETP’s violations go beyond pipeline spills and construction mishaps. A database combining violations and enforcement data across federal agencies (including environmental violations, energy market manipulation, workplace safety or health violations, and pipeline safety violations) shows ETP to have been subject to 146 enforcement actions and fined more than $355 million since 2000.[165] Among fine and violations included in this database, ETP is among the worst-ranked pipeline companies, followed by Enbridge (42 violations, $248 million in fines) and Kinder Morgan (127 violations, $164 million in fines).[166] These violations involve labor practices, workplace safety, clean air violations, market manipulation, and others.[167]

ETP’s Track Record of Spills and Violations

Since 2002, PHMSA has issued 106 violations against ETP and Sunoco and related subsidiaries, and fined them $5,675,870. These violations include failures to inspect crossings under waterways, failures to repair unsafe pipe for five years, failure to report unsafe conditions, repeated failures to properly notify emergency responders and the public, and others.[168]

The construction of the Rover and Mariner pipelines have been marked with spills, environmental violations, and stop-work orders. The two pipelines are designed to transport natural gas and liquids from the Utica and Marcellus shale production areas. By March 2018, after only 13 months of construction, Rover had spilled more than 2.2 million gallons of drilling fluids, industrial waste, and/or sediment, amassing more than 100 violations/non-compliance incidents and four stop work orders for failure to comply with environmental regulations. Mariner construction has led to 108 “inadvertent” releases in numerous locations along the route, leading to more than 50 violations, and several reports of private water wells being impacted by construction activities.[169]

Assuming the U.S. system-wide rate for significant crude oil spills[170] of 0.001 per year per mile, Greenpeace USA has projected that the DAPL and its southern component ETCO would suffer 96 significant spills and Louisiana’s Bayou Bridge Pipeline would suffer eight significant spills, during a 50-year nominal lifetime.

ETP and its subsidiaries also reported 58 incidents to PHMSA from their extensive natural gas pipeline network. Natural gas pipelines bring with them risks of explosions and exposure to harmful substances; in 2017, for instance, a home in Texas was reportedly sprayed with hydrogen sulfide gas and natural gas condensate after the rupture of ETP’s nearby, mostly unregulated natural gas gathering line.[171]

In 2005, Sunoco’s Pennsylvania refineries were subject to a comprehensive Clean Air Act settlement that included a $3 million civil penalty, $3.9 million spent on supplementary environmental projects, and $285 million to install emissions controls.[172] The settlement was aimed at reducing emissions of nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide, hazardous air pollutants that can “cause serious respiratory problems and exacerbate asthma in children.”[173] In 2018 Sunoco (along with BP and Shell) agreed to pay the State of New Jersey $64 million to settle a lawsuit alleging contamination of groundwater from the gasoline additive methyl tertiary butyl ether.[174]

An analysis of EPA’s 2015 Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) data conducted by the Political Economy Research Institute[175] placed ETP among the “Toxic 100 Air Polluters,” ranking ETP 75 in air toxics pollution[176] and 83 in greenhouse gas pollution.[177] ETP also scored poorly on two environmental-justice metrics measuring the impact of air pollution on minorities and people living in poverty, largely because of emissions from the Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery, in which ETP holds a 50 percent stake along with the Carlyle Group. The refinery filed for bankruptcy in 2018.[178] ETP did not rank in the top 100 for water emissions, but pipeline spills are not reported under TRI.[179]

Workplace Safety, Labor, and Other Violations

In general, the oil industry has one of the highest rates of severe workplace injury among its workers.[180] In 2016, workers filed a lawsuit after suffering severe burns and injuries when safety equipment failed while they were servicing a Sunoco pipeline.[181] Since 2000, ETP has been fined 39 times for workplace safety violations, resulting in more than $1.4 million in fines.[182] These include large fines for multiple violations — including repeat and serious violations — found at Sunoco’s facilities in Oregon, OH,[183] Westville, NJ,[184] and Marcus Hook, PA.[185] ETP has been fined three times by the National Labor Relations Board for back wages resulting from “unfair labor practices” totaling $177,000, and five times by the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division, totaling $484,000.[186]

Claims that ETP manipulated wholesale natural gas prices at the Houston Ship Channel hub during a period from 2003 to 2005 led to a “record” $30 million settlement with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission,[187] and an additional $10 million penalty from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.[188] FERC noted that it was the “highest amount of any settlement related to an enforcement action since Congress gave FERC enhanced enforcement authority under the Energy Policy Act of 2005.”[189]

Conclusion

Energy Transfer Partners made numerous mistakes and transgressions during the development and construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Its lack of respect for the rights and the free, prior, informed consent of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe; its continuous disregard of the suggestions and recommendations of government agencies, clients, and international human rights groups; and its condoning of militarized use of force against Water Protectors and allies at Standing Rock are all alarming.

ETP’s behaviour led many banks (including ING,[190] DNB Capital,[191] and BNP Paribas[192]) to formally break ties with the project, selling out their stake in the $2.5 billion DAPL project loan and/or further distancing themselves from the company.

The track record of ETP and related companies on pipeline spills and construction-related incidents is problematic — averaging about one spill every 11 days between 2002 and 2017. Already in 2018, the company has had significant spill incidents and safety violations on its pipelines currently under development, which has led to fines, penalties, and delays. Although it was only completed in 2017, DAPL has already had 7 spill incidents.[193]

Communities living in the shadow of ETP’s pipeline projects, including Rover, Bayou Bridge, and Mariner East 2, have faced harassment, loss of private property, both the threat as well as the consequence of pipeline spills, and more. For those who stand up to the company, some face retaliatory litigation and harsher laws which restrict free speech and freedom to dissent.

Despite global controversy following the events at Standing Rock, ETP and related companies continue to exercise legal tactics and lobbying efforts aimed at silencing opposition, and to retain private security firms with a track record of aggressive tactics. ETP’s unwillingness or inability to learn the necessary corporate lessons from DAPL should raise concerns among the company’s institutional financiers, who are exposed — as they were on DAPL — to the reputational and financial impacts of ETP’s unacceptable practices.

In light of ETP’s ongoing approach to human rights, and its poor record on pipeline spills and safety, we believe that banks should end any current financial relationship with ETP and related companies, and should not provide any further financial services, including loans, to the companies.

Acknowledgments

This report is made possible by the dedicated and thorough drafting and editing of Anne Garland. This report drew heavily on the efforts and work of Water Protector Legal Collective, Earthjustice, which continue to defend the civil liberties and rights of individuals, communities, Tribes, and organizations facing the consequences of Energy Transfer Partners’ efforts to intimidate and silence. Thank you also to the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law for their work on anti-protest bills and their continued efforts to defend the rights and freedoms of all individuals. The movement to stop pipelines has been and will continue to be Indigenous-led. Greenpeace USA is proud to stand in solidarity with Water Protectors, frontline communities, and grassroots leaders who continue to oppose ETP’ pipeline projects.

Endnotes

1. Mr. Alvaro Pop, Dalee Dorough and Chief Edward John, “Statement from the Chair and PFII Members Dalee Dorough and Chief Edward John on the Protests on the Dakota Access Pipeline,” UNDESA, August 31, 2016,https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/news/2016/08/statement-on-protests/.

2. “Free Prior and Informed Consent – An Indigenous Peoples’ right and a good practice for local communities – FAO,” UNDESA Division For Inclusive Social Development Indigenous Peoples, October 14, 2016, https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/publications/2016/10/free-prior-and-informed-consent-an-indigenous-peoples-right-and-a-good-practice-for-local-communities-fao/.

3. “Joint Statement from Department of Justice, Department of the Army and Department of the Interior Regarding D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals Decision in Standing Rock Sioux Tribe v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,” October 10, 2016, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/joint-statement-department-justice-department-army-and-department-interior-regarding-dc.

4. Chief Edward John, Firsthand observations of conditions surrounding the Dakota Access Pipeline, New York: United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, November 1, 2016, https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2016/11/Report-ChiefEdwardJohn-DAPL2016.pdf.

5. “Native Americans Facing Excessive Force in North Dakota Pipeline Protests – UN Expert,” OHCHR, November 15, 2016, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=20868&LangID=E.

6. “Regarding Investigation and Observation.” Margaret Huang to Hon. Loretta Lynch. October 28, 2016. In Amnesty International USA. https://www.amnestyusa.org/pdfs/US_DOJ_letter_Lynch_regarding_investigtion_and_observation.pdf.