The train ride was as uneventful as the dozens of others the man had taken from Washington, D.C., to New York City. He watched the scenery change as he headed north past Baltimore, along the Delaware River to Philadelphia, through Newark, then into the long dark tunnel on the final approach to New York’s Pennsylvania Station. Throughout the trip, the device in his pocket—the size of a portable hard drive, all black, with a single button on the center of one side and a blinking blue LED light above it—remained silent.

After getting off the train, the man moved with the large midday crowd toward the entrance to the subway. On the uptown platform, standing near a dark-haired woman in her late 40s, he felt his pocket vibrate insistently. He looked at his phone: high levels of gamma rays. Technetium-99m. He was the only one who knew. The man, Vincent Tang, is a prominent physicist at DARPA. He and his team have spent the last five years working on Sigma, a program for counteracting nuclear terrorism.

A year ago they launched Sigma+, an expanded system that will identify chemical, biological, and nuclear components, along with explosives, to help law enforcement stop terrorists before they can strike. The major breakthrough is the radioisotope identification device in Tang’s pocket, the D3S, which was built by the British company Kromek. Unlike earlier versions, which were much larger, the D3S fits in your pocket. And at a fraction of the previous price, it can be carried by every police officer, firefighter, EMT, and other emergency-service personnel in a city.

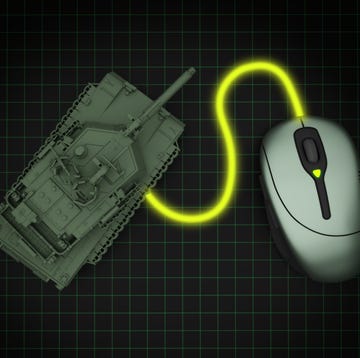

When paired with a network of larger, more sensitive devices, both mobile and at fixed points around a city, this creates a crowdsourced dragnet for thwarting possible biological, chemical, explosive, or nuclear attack.

The Sigma system is already being tested in a few major urban centers across the United States. (They can’t be named for security reasons.) Someday soon, Tang hopes, Sigma+ will be the strongest tool available to cities in the fight against terrorism.

Despite the vibrating in his pocket, Tang isn’t concerned by the reading on the subway platform. Technetium is the most commonly used radioactive tracer, an element doctors give patients before X-rays and other hospital tests. But if it had been an element used for a dirty bomb, Tang would have known just as quickly.

In a Popular Mechanics exclusive, Tang allowed us to test the device in New York City for two weeks. But first he had to show me how it works.

With special tracking software installed on my laptop, Tang demonstrated how simple it was to follow the D3S in real time. Once it was paired with his phone, as easily as you would add any Bluetooth device, the D3S popped up on the map. Had we added more—say, an entire police unit fanned across its precinct—we could have followed them as well and gotten instant notifications of any detected threats.

Next, the test. Inside the D3S is a one-inch cube of thallium-activated cesium iodide crystal. When the characteristic energy of an isotope hits that crystal, it is absorbed and re-emitted as light particles, which are converted into an electrical signal that the D3S reads.

Tang carefully set a palm-size lead container (called a pig) on my kitchen table. Inside were test samples of cobalt-60, cesium-137, and radium-226, elements that, in larger concentrations, could be fatal. He took each out, and we watched as, within one or two seconds, his phone vibrated with an alert—an instant identification of the substance and the approximate amount.

After a little more instruction, I was on my own. In two weeks of very determined testing—and many miles of walking with optimistic suspicion—I’m pleased (but somehow also slightly disappointed) to have found nothing. There was a brief moment of excitement when I passed the foreign embassy of a not-so-friendly country and felt a warning vibration in my pocket. This was it! I thought. I’m about to save the world! But then I looked at my phone: fluorine-18, another isotope regularly used in medical testing.

With older equipment, that false positive, along with the one Tang had on the subway platform, could have sent counterterrorist teams scurrying. New York City wasn’t any safer because of me, but it will be when Sigma+ makes its way to our streets.

This appears in the May 2019 issue. Want more Popular Mechanics? Subscribe!